ROSE PAINTINGS & STILL LIFE

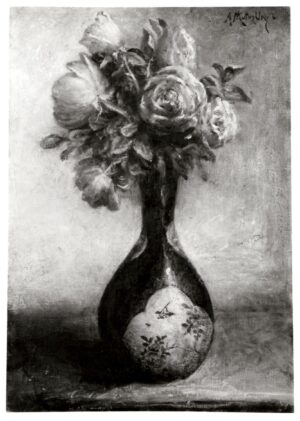

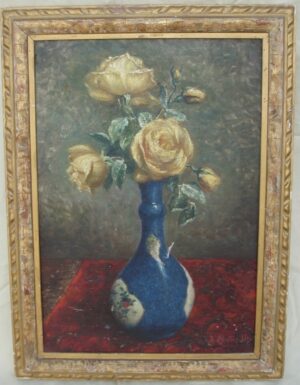

In 1896 A Boston newspaper reported that, ‘… Mr. Muller-Ury, the portrait painter, who has just returned from abroad, has taken an attractive studio in Everett Street, Newport, the one occupied by Mr. Harper Pennington last season. Mr. Muller-Ury’s roses as well as his portraits are admired, and he is painting a huge basket of American Beauties for the Havemeyer villa.’ At Emilie de Loosey Havemeyer’s posthumous sale at the American Art Galleries in November 1914 there were two still lifes, one of American Beauty roses strewn on the grass, and a picture described as: “A tall porcelain vase decorated in color with leaves and flowers, holds three mature American Beauty roses, which rise above it over a mass of their leaves clinging to the stems. Signed at the lower left, A. MULLER-URY. Height, 23 inches; width 14 inches.”

Muller-Ury’s Sherwood studio 1894, showing a still life of a large bowl of roses on the second easel to the left.

In a surviving photograph of the artist’s studio in the Sherwood taken in 1894 (a portrait of Monsignor Satolli is on the easel next to it) there is a huge still life, and in a letter from his studio to James J. Hill dated 12 August 1895 (Hill Papers, St. Paul, MN) he says that he hopes that the ‘flower peace [sic]’ he sent to him ‘will suit for the place intended for’, further evidence that he had painted still lifes before 1896. He is also known to have given still life paintings away as wedding presents: for example on November 10, 1903, a New York newspaper recorded that he sent a still-life of pink roses as a present to Miss Edna Goadby Loew and Mr. Howard Brokaw on the occasion of their wedding the following Wednesday; and it is known that in 1931 he sent a still life to Dorothy Duveen for which letters of thanks from the bride and her father survive in his papers.

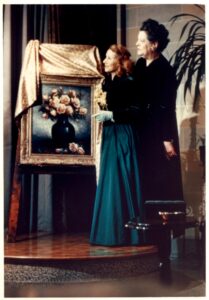

Jessica Dragonette in Milwaukee in 1946 with a Mrs Anderson. It is not known at what event in Milwaukee the Muller-Ury rose painting was displayed. From a labelled slide in the editor’s possession.

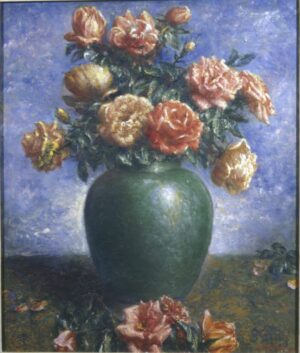

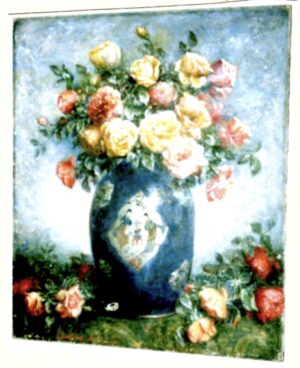

After 1918 he most often depicts roses in Chinese vases from the former collection of J. Pierpont Morgan that he copied in one of the galleries at Duveen Brothers in New York (Duveen’s exhibited the Morgan Chinese porcelain collection in 1919) and elsewhere, and sometimes he included depictions of other works of art like bronzes or bisque statuettes, porcelain Buddhas, Italian Maiolica plates and so on. In some ways, by using vases and other decorative works from the stock of Duveen’s, the artist was indirectly advertising to the clients who might buy his still lifes that they were “buying into” the lifestyle of J. Pierpont Morgan and that which Duveen created for his wealthy clients who bought from his collection.

Muller-Ury with an unknown man in the garden of his San Marino studio, May 1926.

There is evidence that after the artist built his studio in San Marino in California in 1924/5, he painted the vases whilst in New York, and then took the unfinished canvases to his California studio where he painted in the roses. The roses were claimed by the soprano Jessica Dragonette in her autobiography Faith is a Song (1951) to be the varieties American Beauty (red), La France (pink), Belle of Portugal (pale pink), Claudius, Killarney (rose pink), and Boucher-Pierné, but there were many other varieties grown by him in his San Marino garden.

After 1918 the style of his still lifes becomes increasingly impressionistic, his technique more painterly and by the 1940s often uses a great deal of impasto. He told the German Kaiser – who hated the Impressionists – in 1909 that the impressionists had “done a great deal to awaken modern art”, and it is known he was an admirer of the French artists Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir and others, for he recorded in his diaries that on the journey to and from the east and the west coasts he would break his journey in Chicago to study their works at the Art Institute.

During the Depression, as the number of portrait commissions he received became more erratic, and clients sometimes delayed payment or defaulted altogether, painting roses came to dominate his output. This is made obvious by the surviving diaries for 1931-1936 (he records that he painted almost 20 rose paintings in 1933) and the 1937 Wildenstein exhibition handlist where he exhibited 23 portraits (some not recent), four religious pictures, but 28 still life paintings, mostly of roses. Jessica Dragonette wrote that on visiting his studio for the first time in 1940 Muller-Ury showed her ‘…pictures of roses of every color and variety…We were in another world when he showed us the rose paintings. No one could call them still life – they were portraits of living flowers.’

PLEASE CLICK ON A PHOTOGRAPH TO READ THE CATALOGUE ENTRY.