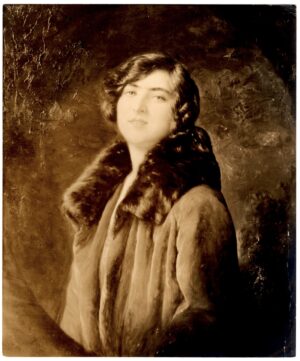

Henry Edwards Huntington was born on February 27, 1850. He married Mary Alice Prentice in 1873, birth sister of his Uncle Collis Huntington’s adopted daughter, in 1910 and married Arabella Wortham Huntington (widow of his uncle Collis Huntington) on July 16, 1913 after Mary Alice’s death. He had four children with Mary Alice (Howard Edward, Clara Leonora, Elizabeth Vincent, and Marian Prentice), but none with Arabella. Arabella’s son Archer, from her prior marriage from which she was widowed, had earlier been adopted by Collis Huntington.

He was a railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. Huntington, though born in Oneanta, New York, settled in Los Angeles where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway, as well as substantial real estate interests. Huntington provided Los Angeles with passenger friendly streetcars on 24/7 schedules, which the railroads could not match. This was facilitated by the boom in Southern California land development, where housing was built in places such as Huntington Beach, a Huntington development. Connectivity to Downtown Los Angeles made such suburbs feasible. By 1910, the Huntington trolley systems spanned approximately 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of southern California. In addition to being a businessman and art collector, Huntington was a major promoter of Los Angeles as a place to live in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In San Marino many places are named after him. Huntington retired from business in 1916 and died in Philadelphia while undergoing surgery on May 23, 1927.

Muller-Ury apparently first met Huntington on March 21, 1922 when he came to Los Angeles with Sir Joseph Duveen who was delivering Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy which Duveen had purchased from Grosvenor House, from the Duke of Westminster, for the huge sum of $728,000 (£182,200 according to copy letter in Duveen archive from HEH to Duveen in Paris October 7, 1921). Edward Fowles records the following anecdote in his autobiography entitled ‘Memories of Duveen Brothers’ (London, 1976) p.148:

The photograph to which Edward Fowles referred in his memoirs, dated by the artist 21 March 1922. Huntington stands to the left, Duveen in the centre, Muller-Ury is to the right (the oriental art dealer Parish Watson is hidden behind the artist).

“It was well advanced in the month of March when Duveen arrived with The Blue Boy at Pasadena. H.E.H. came to the railroad station to meet him. Joe had brought with him an ‘academic’ portrait painter, Muller Ury, in the vain hope that H.E.H. would commission a self-portrait. My description of the scene brings to mind an amusing snapshot which someone sent me at the time. According to the caption, Ury asked H.E.H., ‘Don’t you think you paid too much for The Blue Boy?’ and H.E.H. apparently replied, ‘Duveen didn’t know, but I would have paid much more for it.’ In the snapshot H.E.H.’s mouth is wide open in a huge guffaw; Duveen’s chin, on the other hand, droops in pained consternation.”

Huntington bought Reynolds’ Mrs Siddons as the Tragic Muse in Paris in October 1921 for £37,800 on same terms as Blue Boy (letter in Duveen archive from HEH to Duveen of November 19, 1921), and it was delivered to HEH at same time.

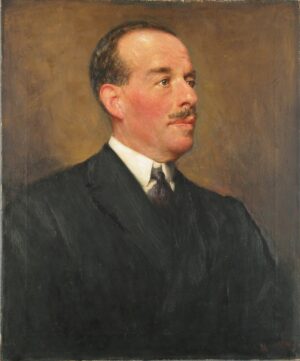

There is no mention of Muller-Ury as a travelling companion in Duveen’s telegram of March 13, 1922 accepting Huntington’s invitation to Los Angeles. It specifically records that Duveen will arrive in Los Angeles at 2.35pm on Tuesday, March 21, 1922. (HEH 10653 – Telegrams). But as the press photograph and Fowles’ memoirs show he travelled there with Muller-Ury and the dealer Parish Watson (HEH 13566 – Letter of thanks from Watson, 14 April 1922). With no portrait commission given to Muller-Ury in 1922, Duveen arranged for Sir Oswald Birley to paint Huntington for a fee of $6000 in February 1923. The painter Ambrose McEvoy had painted Huntington in 1921 and Huntington was apparently billed $4500 for this, although Duveen tried to claim $6000 as he had advanced this sum to the artist (letter in Duveen archives from Duveen to HEH, December 27, 1921), but the picture was not satisfactory (letter in Duveen archives from HEH to Duveen, March 6, 1922). The commission to Birley is very curious as on Friday October 26, 1923 Muller-Ury wrote a card to Archbishop Hanna of San Francisco (Chancery Archives, Archdiocese of San Francisco) which reads:

‘Most Rev. Archbishop & dear friend,

I am leaving today for Pasadena with Sir Joseph Duveen & will probably be there only 5 days & return again to New York stopping 2 days in Chicago…Sir Joseph Duveen is bringing 3 marvellous paintings – to Huntington & he wants me to arrange about painting Mr. H. Huntington for his gallery. I will be at the Huntington Hotel as I don’t want to stop at H.H. house…’

But again no commission to paint Huntington was forthcoming, though perhaps Duveen was still trying to persuade Huntington to have a portrait of himself in the house and not just the library.

Muller-Ury evidently travelled again to Pasadena with Duveen in November 1924 (Duveen had arrived in Los Angeles from Chicago on November 23, 1924 at 2 pm, having left NY on 15 November), as the artist was buying the land for his new studio in San Marino from the Huntington Land Improvement Company (Duveen bought the plot next door). On December 4, 1924, he wrote to Archbishop Hanna in San Francisco from the Vista del Arroya Hotel to inform him that he had decided ‘to build a studio and little home here at Pasadena.’ The idea was, he confided, to spend the four months of the winter each year working in the warm climate, and excitedly he told him that ‘Mr. Huntington and few other very artistic people seems to exhibit such enthusiasm for my plans, and so I certainly ought to be charmed with the realisation to come and live with such atmosphere.’ He added later in the letter that his friend ‘Sir Joseph Duveen has bought a lot next to me here to build a Bungalo (sic) and so come once a while to stay near me.’ (Chancery Archives, Archdiocese of San Francisco). By the late summer of 1925 the San Marino studio was finished and the artist moved in and on January 9, 1926 Duveen wrote to Huntington admitting that ‘…Although we are three thousand miles away, I hear all about you from Adams [employee of HEH his in New York office] and also from Müller-Ury…’ (HEH 10699) This suggests that the artist saw Huntington quite often. In June 1925 Duveen published a catalogue of the British Paintings he had sold to Huntington, and sent a list of the persons to whom he had sent copies. It is interesting that in another list prepared by Duveen’s gallery in New York in April 1926 it states that Muller-Ury received (20) and (12) copies of the catalogue in Pasadena; presumably this was so that the artist could give them to Duveen’s clients and friends when they were in Los Angeles and visiting Huntington’s gallery.

Huntington had an operation in the autumn of 1926 and Muller-Ury clearly called on him often and chatted with him when he was recuperating. It may have been at this time that the artist finally persuaded Huntington to let him paint his portrait. It is certainly known that in March 1927 Huntington informed Duveen in a letter that Muller-Ury was painting his granddaughter Mary Brockway Metcalf. But Huntington remained mortally ill and died in Philadelphia after another operation two months later, just around the time the artist had broken his leg in a fall in the garden of his San Marino studio. The artist wrote to Elizabeth Huntington Metcalf on 28 May 1927 a letter of condolences in which he said: ‘I will always be happy to realize that I have known such inspiring personality & will consider the greatest priviledge (sic) of my life to have seen so much of him.’ (Elizabeth Huntington Metcalf Papers, Box 1926-7).

—

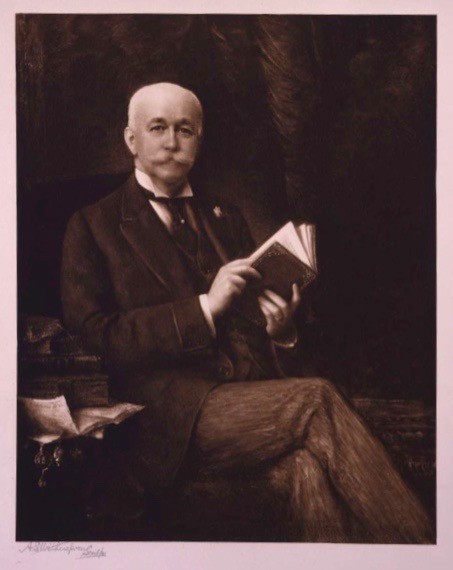

Muller-Ury presumably had began the larger seated portrait just before Huntington died (but whether from life or not is unclear and perhaps unlikely as Huntington was seriously ill); Metcalf sent Muller-Ury a photograph at the end of June 1927: “the best of any which we have.”). He then completed a large and a small seated portrait and a standing portrait from another better-known photograph. John B. Metcalf and his wife Elizabeth Huntington, and Mrs Huntington – the widow of Henry Huntington’s son Howard – considered purchasing a portrait of Henry Huntington from Muller-Ury for presentation to the Art Gallery of the Huntington Library in San Marino from the time of Huntington’s death in May 1927. But despite painting three portraits of Huntington nothing seems to have happened for nearly five years, partly as a result of the legal necessities required in turning Huntington’s home and library into a public institution.

The matter was taken up, however, when John Metcalf wrote to the artist on September 13, 1932. It would seem that Muller-Ury was prepared to give the family a portrait of Huntington (Metcalf indicates that this would be the “one with the book is much better suited to the house than that standing”) which they would then present to the Art Gallery:

“…We appreciate your offer of the portrait very much indeed; personally I am much pleased with the work. You have been able in a large degree to get the individual.

Before taking up this matter with the Trustees of the Library I should like to know your wishes in this regard. Such will have to be done though I shall do it in an informal way and really it is your gift though arrived at indirectly.

Please be quite frank about it…”

In an undated fragment of a letter to Muller-Ury from Metcalf he writes as follows:

“…Your portrait of Mr. Huntington as I have told you before pleases us very much and we should be more than glad to have it hung in the Gallery. I have no doubt that the Trustees will feel the same way about it. I think it is far better than any portrait of Mr. Huntington extant and in it aside from the artistry you have succeeded in portraying the man himself to a wonderful extent. I am sorry that you yourself cannot present it to the Gallery as yours is the honor though I understand your feelings in this regard. You realise I am sure that a gift from the family where it is as personal as this must be handled with delicacy. We appreciate your position in the entire matter and your generous intent.”

It could be that Muller-Ury felt that, considering his friend Duveen had persuaded Huntington to commission portraits of Huntington and his wife Arabella from Sir Oswald Birley, he could hardly appear to be giving pictures away without payment, and that to an institution whose Founder had not commissioned him to paint his portrait when he was alive. Then in a letter dated April 21, 1933 Metcalf wrote to say that he had withdrawn the whole offer of a gift of a portrait from the family. He said that he had contacted the Trustees unofficially, and consequently the family were unable to act freely and just give the picture, but that in any case “…they do not respond in the way that you and we would wish them to before making such a presentation.” Furthermore, Metcalf indicated that he had told the Trustees that he did not want the gift to hang in the Library block which was the Trustees’ tentative place for it. The matter, however, appears not to have ended there, for there is a letter dated July 22, 1933, from Max Farrand, the distinguished historian, who was Director of Research at the Huntington at that time, which states explicitly that Mr. Henry Robinson, one of the Trustees whom Muller-Ury had painted earlier in his time in California, had been to see the two pictures at Muller-Ury’s studio, and had preferred the standing version. This seems to indicate that Robinson’s opinion carried great weight amongst the Trustees, much to Metcalf’s and Muller-Ury’s regret. Farrand ended his letter, “…After reviewing the whole question, therefore, I see no reason for revising our former conclusion./ Regretting the necessity of writing to this effect…” (All letters quoted in artist’s papers)

—

Started in early 1927 (and completed from June 1927 with the aid of a photograph supplied by Lawrence V. Metcalf).

The oil painting was engraved by Arthur S. Witherspoon Sculpt. A copy is now in the American National Portrait Gallery (Provenance: The artist; Jessica Dragonette; her husband Nicholas M. Turner’s gift to the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center, 1987; their gift to present owner, 2007.) Another copy is in a Private Collection, London, UK (Gift to the present owner from the late Bobbie Kester of Beverley Hills, 1991 whose mother-in-law Maude Kester was given it by the artist.)

Duveen had recommended Witherspoon to Huntington for the engraving of the plates of his catalogue of ‘Some of the Paintings of the British School…’ in a letter dated February 13, 1923 (Huntington Library: HEH 10671) saying that he had engraved the plates of the catalogue of the collection of Henry Goldman and had formerly been with the famous De Vinne Press (closed 1922). Witherspoon & Arata were at 30 East 42nd Street, New York in 1924 (letter in Duveen archives from A. Witherspoon to Sir Joseph Duveen, February 7, 1924 re: plates for the Huntington catalogue).