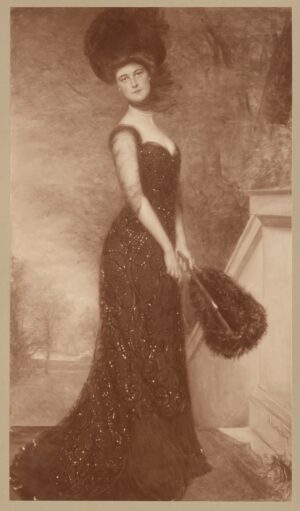

The sitter was born Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert, on 27 January 1859 and died 4 June 1941, was the last German Emperor (Kaiser Wilhelm II) and King of Prussia reigning from 15 June 1888 until he abdicated on 9 November 1918 shortly before Germany was defeated in World War I. He was the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria and related to many monarchs and princes of Europe, most notably his first cousins King George V of the United Kingdom and the Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II.

—

The history of this portrait and the context of the commission has been published in an article by the editor of this website: Stephen Conrad, “Re-introducing Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862-1947): The artist, two dealer, four counts and the Kaiser: a hitherto unknown episode in international art history” in The British Art Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, (2003) pp. 57-65.

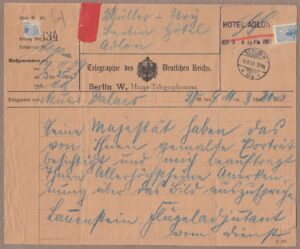

The portrait was a commission from Herman Ridder of the New-Yorker Staats Zeitung. Through the auspices of Senator Depew, Muller-Ury was brought firstly to the attention of the American Ambassador to Germany, the Hon. David J. Hill, by letter at the end of May 1909 (letter in the artist’s papers). Certainly Herman Ridder received a letter from the Kaiserlicher Geschaftstrager G. Wedel on July 31, 1909 (copy, same source) which told him ‘…in der zweiten Halfte des Oktober im Neuen Palais einige Sitzungen…’ in which Muller-Ury could begin the portrait. Ridder sent a telegram to Muller-Ury through Duveen Brothers’ gallery at 21, Old Bond Street, London, on September 7, 1909: ‘emperor gives you sitting end of october.’ The cable crossed with a letter from the artist, and Ridder had to send another cable, and then another letter repeating what was in the cable: ‘Communicate with Oberhofmarschallamt Berlin immediately as stated in Wedel’s letter’ and expressing in slightly irritated terms that he could assist him no further. The artist did so, and was told by reply to present himself at the Neuen Palais on October 23 (same source). On October 12, the Berlin correspondent of the New-Yorker Staats Zeitung, Gunter Thomas wrote to Muller-Ury with useful advice and indicating persons whom it might be useful for him to contact in Berlin (same source). According to the New York Times dated October 24, 1909, the artist was to receive the first sitting from the Kaiser ‘tomorrow’. The sittings must have been completed by November 9, 1909, for on that date the artist received a telegram at the Adlon Hotel in Berlin — the grand hotel where rich Americans used to stay — from the Flugaladjutant at the Neuen Palais with a message from the Kaiser. On November 16 the artist wrote the following suitably obsequious letter to the Kaiser:

‘Majesty!

Before leaving your Great Nation, I take the liberty to thank Your Majesty for innumerable kindnesses and for the sacrifize Your Majesty was obliged to bring for art sake again! Nobody in the world ever appreciated more Your Majesty’s sittings than Your Majesty’s most humble servant – & if I had succeeded to please a little with my work Your Majesty it would be the greatest recognition & the greatest delight I ever expect to have in my life. — I was enchanted with the Marienburg & never would I have ever dreamed that I admired in Braunschweig not only the interesting artistic houses but those great art creations & specially Rembrandt — Hildesheim is a delight for any lover of antiquity.

I hope Your majesty has deigned to sign “Kaiser und Kunst” wich I left with Your Majesty’s Adjutant, as it would be the most cherished possession of my Library.

Expressing to Your Majesty my most heartfelt Gratitude,

I remain

Your Majesty’s most humble Servant

A. Muller Ury’

(copy letter, same source). Indeed, it is known that the Kaiser complied with the artist’s request to sign a copy of ‘Der Kaiser und die Kunst’ by Paul Seidel, Berlin 1907, because the volume was Lot 22 in the sale of the artist’s property at the Plaza Art Galleries, 9 & 11, East 59th Street, New York, on Friday, November 28, 1947.

The telegram the Kaiser asked his Adjutant to send Muller-Ury at the Hotel Adlon in Berlin.

By November 25, 1909, the artist was back in New York and told the press of his endeavours. In the reviews it is mentioned that the artist received 10 sittings totalling 32 hours from the Kaiser. In Germany prints were made of the picture by Gurlitt before being sent for exhibition in Berlin at ‘Die Amerikanische Kunstaustellung der Berliner Akademie der Kunste’ from March 22 to April 30, 1910 (bit it was not listed in the catalogue as it had already gone to press). According to a letter the artist wrote to Senator Chauncey Depew on December 5, 1909 (Yale University Library, Depew papers MS180, Box 3, Folder 79) he left the portrait in Berlin specifically for this exhibition ‘at the request of the Emperor’, and added in a postscript that the Emperor considered the portrait ‘the best ever painted of him’. The picture must have been sent finally to America in October 1910, when the artist himself returned from Europe from a holiday.

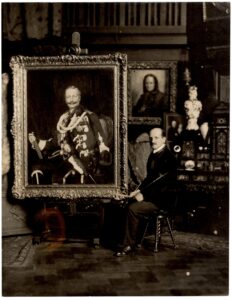

Muller-Ury photographed with his portrait of the Kaiser in his studio in the Atelier Building, 33 West 67th Street, New York, in 1910. In the background may be seen the 1905 portrait of the artist’s mother.

It was not widely exhibited in America, and the press rumoured it would be given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which did not happen. The facts are that on December 12, 1910, Herman Ridder, wrote to Mr. Nicholas Murray Butler offering the picture to the Deutsches Haus of Columbia University in the City of New York at 419 West 117th Street. This was accepted and acknowledged by the latter on December 21, 1910. The portrait, however, did not go straight to the University but was exhibited at Knoedler’s in December 1910 and January 1911. It was announced in the Columbia Alumni News in 1911 that, ‘It is proposed to hang this fine portrait in the new Deutsches Haus.’ The artist evidently borrowed the picture sometime later and kept the picture longer than he should have done for Mr. Rudolf Tombo Jr. wrote to the artist in September 1912 saying “…I hope that you will return the portrait of the Kaiser as soon as possible, as the University will be opening shortly, and there will be many visitors to the Haus daily.” (All letters, same source)

The New York Evening Post, December 21, 1910 reported that ‘…Mr. Ury is to be congratulated on the painting, for, though it is practically an official portrait and he has flattered his sitter and made him much younger than the Kaiser is, he has, at any rate, given it life. He has made good use of the handsome costume of the Black Hussars and of the marshal’s baton, which the Emperor holds in his right hand, and so given us a picturesque portrait.’ The Globe, December 29, 1910 called it ‘…an official portrait – and any representation of so august a personage must be official – it is much more spontaneous than such works usually are, the artist securing an admirable likeness and considerable freedom to his painting. Certainly his majesty is a good looking man to inspire any painter and Mr. Muller-Ury has not escaped the sovereign’s blandishments. William looks every inch the soldier, the man, and the head of government, and the work is quite the best we have seen from Mr. Muller-Ury’s brush.’ The New York Evening Mail of December 29, 1910 disagreed, saying that ‘…in point of social importance, though not in artistic merit, is the portrait of the German emperor which Mr. Ury painted in 1909. It shows us an elderly, care-worn, rather pallid and saddened kaiser, with somewhat of the ferocity of his tip-aspiring mustaches abated, and a general aspect of weariness of his job. The picture lacks the spontaneity, the warmth and the power of the fine portrait of James J. Hill which hangs near.’ However, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 30, 1910 described the picture with its ‘…spontaneity of the drawing and in his faithfulness in depicting the ruddiness of the health the emperor enjoys, judging from his countenance, and his slightly graying hair…The portrait was made evidently only after an intimate study of the emperor and the man, and the painting in its high key is suited to the character of the sitter.’

The New York American of January 2, 1911 devoted its review to arguments about ‘the importance of truth’:

‘…That is what sitters seek.

They do not care to be told that pictures meant to represent themselves are admirably painted; they want to hear words of praise regarding their resemblance. And the Muller-Ury portraits are to show significantly that their painter has learned to please.

Perhaps his sitters forbade flattery; perhaps their pride made of it a mockery, or, more likely, Muller- himself is opposed to everything in the nature of a rebellion against truth. His portraits do not flatter, and he has attempted to make of them, not beautiful works of art, but documents that may go down to posterity as associated facts purely.

His portrait of Kaiser breathes a fidelity that must be said to further this argument. It is executed with the assistance of art – art that compromises with commonplaces at the invariable expense of conscientious reproduction. The Emperor’s tailors and bookmakers should be as pleased by this likeness as the Emperor’s relatives. Muller- has slighted neither the Emperor’s face nor the Emperor’s boots and his costume, that of a Black Hussar, is painted with a wealth of unashamed detail that is poor only in that it slights the stitches by which the suit is held together. A camera would not have made quite so justifiable a job of it.

And then too, it presents to America a new view of the Kaiser, whom it has learned to look upon as ferocious. That is where honesty holds the sway that is properly its due. To see the royal personage as Muller- sees him is to know him better, perhaps. He is calm, docile, tractable – he holds the pose with as much rigidity and ease as would one of those painter’s dummies that are delightful in studios because they do not insist, with a wave of the thumb, upon voicing incombatable [sic] and useless arguments on art and are ever, with originality there, silent.’

Another photograph from 1910 of the artist with his portrait of the Kaiser.

The New York Evening Post, Saturday, April 5, 1913, p. 9, remarked that some of the works he was exhibiting at Knoedler’s ‘are not without some study of form, as for example with the rather dry and colorless portraits of Emperor William of Germany and Cardinal Farley.’

Part of an anonymous and undated Italian New York Newspaper article (possibly, Il Progresso Italo-Americano, ceased publication 1988) in which the portrait of the Kaiser was rediscovered.

The photographs taken of Muller-Ury seated before the canvas in his studio in New York was reproduced in, amongst other places:

Die Schweiz, October 1, 1912, p.462.

The Zurcher Illustrierte, No. 4, January 27, 1939, XV Jahrgang, p.108.

Karl Iten, URI: Die Kunst- und Kulturlandschaft am Weg zum Gotthard, 1991

p.245.

The picture was most likely taken down and placed in storage at the University when America declared war on Germany in 1917, and according to information supplied to the editor by the University it was disposed of by a committee including Professor Julius Held in the 1960s. It reappeared in the hands of a San Marinese picture restorer of 209 East 59th Street in New York called Carlo Wilson Reffi at around this time, who apparently bought the canvas in a junk shop torn and abraded and cleaned off its surface an abstract, to reveal Muller-Ury’s picture of the Kaiser beneath. This story may be doubtful. The picture has not been traced since it belonged to Reffi, who probably died in the 1970s according to the Italian Cultural Institute in New York.