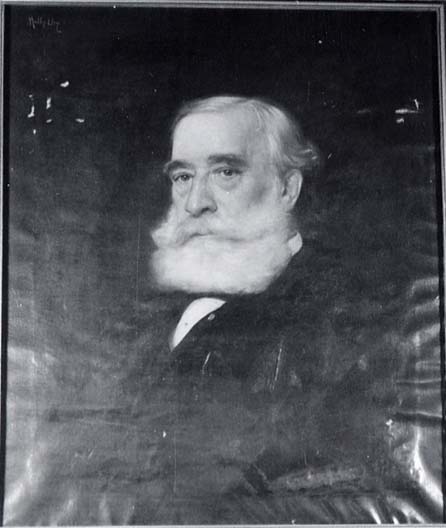

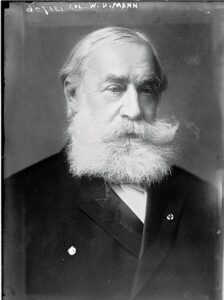

A photograph of Mann shortly before he died.

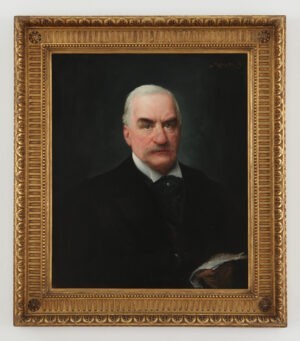

The sitter was born in Sandusky, Ohio onSeptember 27, 1839 and died on May 17, 1920. He was educated as a civil engineer, but enlisted in the Union Army at the outbreak of the Civil War, rising from Captain to Colonel in 1862. After the war he settled in Mobile, Alabama, developing the production of cotton-seed oil. He entered politics and was elected to the 41st Congress, but was not seated. He patented the boudoir car in 1871, becoming a founder of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits, and the Mann Boudoir Car Co, which was later bought out by Pullman Co. From 1891 he was the president and editor of Town Topics; he also founded a magazine called ‘The Smart Set.’ He was married at least three times, lastly in 1902 to Sophie Hartog; his daughter Emma was the offspring of his first.

Bibliography: Andy Logan, The Man Who Robbed the Robber Barons, New York, 1965.

—

Muller-Ury began the portrait of Mann in the middle of October 1902. The New York Herald, October 19, 1902, reported that ‘…Colonel Mann’s leonine head and his ruddy face, framed with snowy hair and whiskers, should make him an excellent subject for Mr. Muller-Ury’s brush.’ When finished, inevitably, Town Topics, November 27, 1902 commented favourably on the portrait of its proprietor: ‘…Mr. Ury’s friends will be pleased to note that his work has broadened a great deal in recent months. His portrait of Colonel Mann, particularly, is rendered with considerable freedom and vigor, and in this respect is the best work that the artist has produced. The portrait is fair in color, a good likeness – although the mouth is perhaps unnecessarily severe – and the downy quality of the white hair and beard is especially well painted…’ The other critics, however, when viewing the Noe exhibition were not inclined to disagree, and said of Mann’s portrait that it was ‘thoroughly good in every way’ (New York Herald, January 11, 1903) and ‘a speaking likeness and the character well-caught’ (Art Interchange, February 1903). Muller-Ury was to be a guest of Colonel Mann at Waltonian Island in late August 1904, a private island in Lake George opposite the town of Hague.

When Pope Pius XI knighted the artist in March 1923 Emma Mann-Vynne wrote to Muller-Ury on March 3, 1923, from Florida (artist’s papers) saying that she was inserting a notice about this in the next issue of Town Topics, and added the following ‘…My dearly loved father truly appreciated your work, and I value your portrait of him more than any possession I have in the world…’ Mann’s daughter, first married in 1896 Harold Vynne, a Town Topics editor and contributor, but were divorced in 1898, and he died in June 1905; her second husband was a lawyer called Albert A. Wray from whom she was divorced in 1912. She added the hyphen to her name after her first divorce and reverted to this form of her name after her second divorce. She died aged 66 in December 1924.

This picture was inventoried in Michigan in 1939-1940, when it was mistakenly identified as US Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes; it was probably acquired earlier, possibly from members of the Mann family who lived still in Michigan, Ohio. The picture is in unrestored condition.

In 2020 the editor was contacted by an art appraiser about a portrait of Mann which had descended from cousins of the family of the sitter in Florida; the family also possessed a sword which had belonged to Mann and was inscribed with his name, as well as other memorabilia. The portrait, which was a pastel and not an oil, showed Mann at least ten years older than the current portrait, much more like the photograph posted here, and showed Mann wearing exactly the same lapel pin; it was signed Pach, presumably being by the young Walter Pach who had trained as an artist long before he was involved with the avant-garde and the 1913 Armory Show. Its appearance does not of course explain how the oil portrait left Emma Mann-Vynne’s possession and ended up in Michigan.